Bulgaria is holding parliamentary elections this Sunday (2 October), a snap vote triggered by the fall of Petkov’s government in June 2022. Bulgarians head to the polls for the fourth time in a year and a half, as a series of snap elections (July and November 2021) and a regularly scheduled election (April 2021) have failed to bring political stability to the country.

The current frontrunner for the Sunday election is GERB (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria), a centre-right party led by a veteran of the Bulgarian political scene and former Prime Minister, Boyko Borisov. GERB is trailed by the “We Continue the Change” alliance, a political movement headed by Asen Vassilev and the incumbent Prime Minister, Kiril Petkov. Several other political parties and coalitions are currently polling above the electoral threshold of 5%, including the left-wing Coalition for Bulgaria, the Turkish minority party DPS (Movement for Rights and Freedoms), the far-right party Revival, the centrists at Democratic Bulgaria and big-tent party There is Such a People.

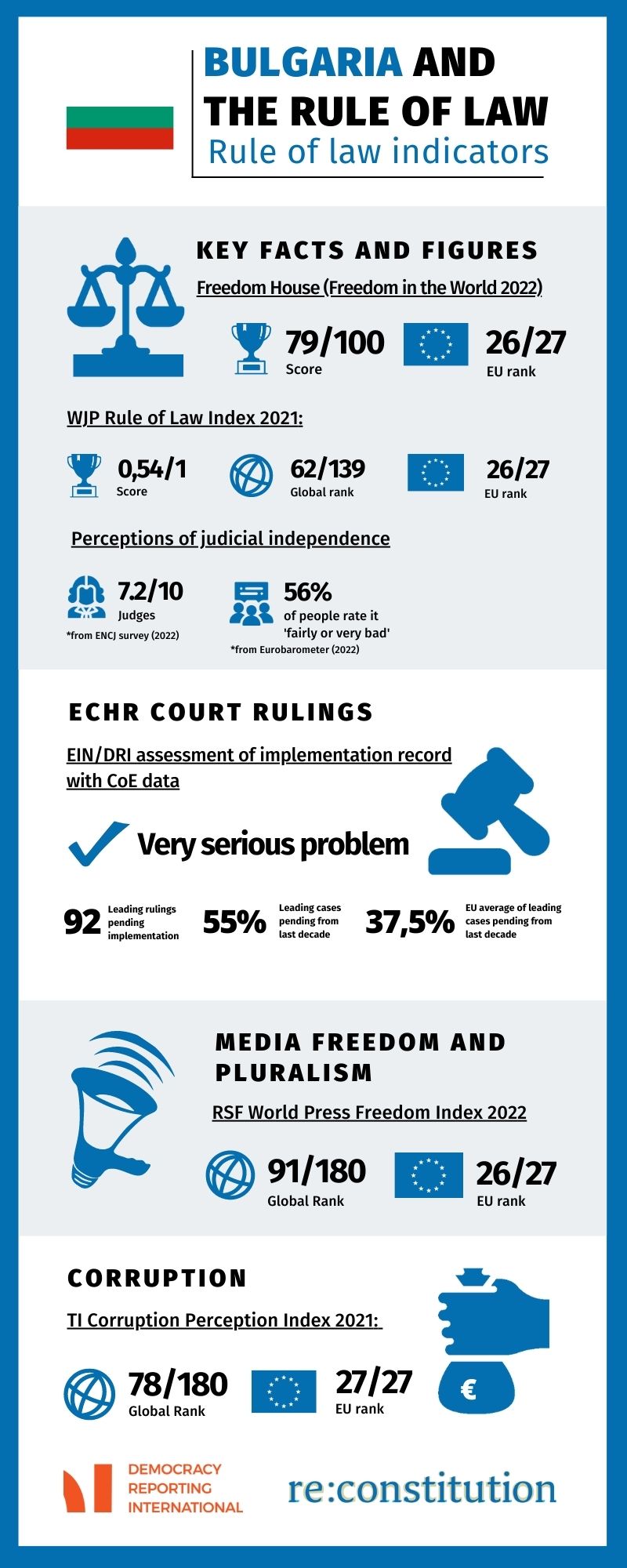

Click on the infographic above to view it in full resolution

Despite a high chance for an outright victory by GERB, the prospects for it securing a parliamentary majority are unclear, and Bulgaria could again face a deadlock, a majority unable to establish a government. Such an outcome would sink the country even further into the political instability persistent in the country since 2021. Problems in regards to the rule of law and the issue of corruption —which plagued Bulgaria during the previous Borisov governments — complicate GERB’s chances to find allies among other parties. A lot of these other parties ran, to various degrees, on a platform against GERB. On the other hand, the alliance which led to the formation of the Petkov government fell apart after the party There is Such a People pulled out, making the prospect of forming a coalition without GERB equally questionable.

Bulgaria’s rule of law record remains one of the worst in the European Union. In several areas the country ranks lower than states mostly associated with the rule of law crisis, such as Hungary and Poland. Corruption, independence of the judiciary, the position of the prosecutor general and media freedom remain significant problems. The country is formally still under the European Union’s Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM), which is meant to strengthen and improve the rule of law in Bulgaria and Romania. All those issues are confounded by the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, which adds a layer of complexity to a country with a robust pro-Russian sentiment. Bulgaria is nevertheless supporting Ukraine with military and humanitarian aid and backing EU’s sanctions against Russia.

Top rule of law challenges in Bulgaria

Bulgaria’s rule of law performance is very low, way below the EU average. The most prominent rule of law challenges are related to (1) justice system (2) media freedom (3) anti-corruption efforts and (4) the prosecutor general.

Click on the infographic above to view it in full resolution

Justice system

Low levels of perceived independence of judiciary: The perceived level of independence of the Bulgarian judiciary is low. Only 31% of the general population and 28% of businesses rank the independence of the judiciary as good or very good, according to the 2022 EU Justice Scoreboard. Both figures have decreased compared to previous years. Bulgaria has not witnessed a full-on capture of the courts by political parties or a reshaping of the judiciary to the extent present in Hungary and Poland. However, the perception of deteriorating independence of Bulgarian judges, mainly linked to widespread issues of corruption and undue private influence, continues to vex the country.

Issues with judicial self-governance: The composition and functioning of the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) of Bulgaria continue to be an issue, with ex officio judges forming a majority over peer-elected judges. This is further exaggerated by an outsized role of the Prosecutor General in the Council. The role of the SJC in the disciplinary proceedings against judges is also seen as problematic, particularly in the wake of the ECtHR judgment in the case Todorova v Bulgaria. In that case, the Court found that disciplinary actions taken against a judge over her public statements were incompatible with the right to a fair trial under Art. 6 (1) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Delays in the implementation of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR): As of 1 January 2022, Bulgaria had 92 leading judgments (judgments addressing systemic or structural issues) pending implementation. Bulgaria’s rate of leading judgments from the past ten years that remained pending was at 55% (European average: 37,5 %). Under the categorisation proposed by the European Implementation Network and Democracy Reporting International, Bulgaria’s implementation record presents a “very serious problem”. The other states falling under the same category are Hungary, Italy and Romania. Some of the vital non-implemented judgments concern: fines and convictions for journalists (Bozhkov v. Bulgaria, pending since 2011) and lack of registration of associations representing minorities (Umo Illnden and others v. Bulgaria, pending since 2006).

Prosecutor General

Lack of accountability: The issue of the lack of provisions for carrying out a criminal investigation into the activities of the Prosecutor General and their deputies is unresolved, resulting in a de facto complete immunity of the Prosecutor General from criminal liability. This arrangement contributes to an outsized power and role for the Prosecutor General in Bulgarian politics and the legal system. As part of reforms agreed by the Bulgarian government with the European Commission towards implementing the Resilience and Recovery Facility (RRF), Bulgaria committed to a wide-ranging reform of the Prosecutor General, including improvements to handling their criminal liability.

Early termination: Earlier this year in February, the Constitutional Court of Bulgaria ruled that the Minister of Justice may request the Supreme Judicial Council to end the term of the Prosecutor General earlier than expected. This paved the way for two attempts to remove the incumbent controversial Ivan Greshev, both rejected by the Supreme Judicial Council. Concerns persist that under the current legal framework, the Prosecutor General is effectively irremovable from the office, with the Supreme Judicial Council firmly allied with him and refusing to honour ministerial requests for an early dismissal of Greshev.

Media Freedom

Weak regulatory framework: Experts are concerned about the independence of one regulatory body (Council for Electronic Media) and the effectiveness of another (National Council for Journalistic Ethics). The laws on transparency of media remain insufficient, with several outlets failing to disclose their ownership. Similarly, problems persist regarding state advertising regulations, media concentration and independence of public media. While the 2022 EU Rule of Law Report notes improvement in several of the abovementioned areas, the legal framework for Bulgarian media is still deficient.

The situation of journalists: While slight improvements have been noted recently, Bulgarian journalists face some of the most significant risks in all EU Member States. Increased use of SLAPPs, attacks and harassment of journalists are coupled with long-standing issues regarding access to public information and a lack of a culture of accountability of politicians before the media.

Anti-corruption

High level of corruption: Bulgaria remains a country with a significant level of perceived corruption. Major indices show a high yet stable level of perception of corruption among businesses and the general population. Corruption has been one of the biggest issues in Bulgaria since 1989. The country’s entry into the European Union was coupled with establishing the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism to, among other things, help lower the level of corruption.

Impact of EU RRF: In addition to several ongoing reforms of the Bulgarian anti-corruption framework, the government pledged to implement a slew of reforms as part of the European Commission’s agreement on the disbursement of RRF to Bulgaria. These include a reform of the Anti-Corruption Commission, an implementation of the National Strategy for Prevention and Countering of Corruption and the introduction of a verification mechanism for enhancing the integrity of civil servants.

Lack of effective prosecution of corruption-related crimes: Despite some improvements in the regulatory framework, one of the most significant persistent issues regarding corruption in Bulgaria remains the lack of effective prosecution of high-level cases. This situation is reflected in the persistent perception that while low-level corruption is being prosecuted, high-level cases, particularly those concerning politicians and high-ranking officials, are not being adequately investigated. Citizens then perceive a culture of impunity among authorities. This year’s high-profile arrest of former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov on charges related to misuse of EU funds, followed by his quick release, is a prime example of the challenges Bulgarian authorities face when prosecuting high-level officials.

What’s next for the rule of law in Bulgaria?

Current polls indicate that whoever wins the elections will face a mounting challenge to establish a large enough coalition to secure a majority in the National Assembly. The three most possible outcomes are either a coalition assembled around GERB, one built by the We Continue the Change movement, or a parliament unable to generate a governing majority. Under the first scenario, the GERB-led government will find itself in a situation where its predecessors have initiated significant rule of law-oriented reforms. These reforms have been aimed squarely at dismantling elements of law and policy put forward by GERB long before. The preceding governments have also committed to RRF milestones and obligations that are contrary to GERB’s policy. If Boris Borisov were to assume the post of Prime Minister again, he would be under significant pressure to keep the course of reforms in order to ensure that Bulgaria continues to receive RRF payments.

Under the second scenario, with a government likely again led by Prime Minister Kiril Petkov, one can also expect a strongly pro-European and pro-Ukrainian course, coupled with continued attempts to improve the independence of the judiciary and prevent corruption. The biggest question is whether such a coalition will be stable enough to maintain its reformist agenda and fulfil Bulgaria’s rule of law-related obligations under the RRF deal. Another open question is whether this frail coalition would be able to overcome multiple legacy issues with the country’s judiciary, prosecutors and corruption.

The third, most worrying scenario is that no coalition will be able to secure a majority in the National Assembly, pushing Bulgaria deeper into a political crisis and likely triggering another election. That is unless the political parties agree on some solution, such as a technocratic government. However, the deep divide between the political movements and a lack of a culture of political party cohabitation does not bode well for such as solution. Were Bulgarians to head to the polls for the fifth time in a relatively short time span, fatigue and disillusionment with the political class could set in deeper and pave the way to radical movements dramatic upending of the current political consensus.

Perspectives of re:constitution fellows

The perspectives below, brought up by re:constitution fellows, do not represent the views of Democracy Reporting International, but those of its authors.

Dr. Stoyan Panov, re:constitution fellow 2019-2020, a Lecturer in International Law and EU Law at University College Freiburg, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg.

The upcoming parliamentary elections on 2 October 2022 in Bulgaria may have significant implications on the reforms related to judicial independence and anti-corruption framework as outlined in the EU’s 2022 Rule of Law Report and the RRF. Bulgaria has to implement various reforms in the anti-corruption sector, laid down in the NextGenerationEU framework, such as the revamping of the Anti-Corruption Commission in two bodies, namely a confiscation and asset-recovery organ and an anti-corruption investigation commission. The institutional reforms are necessitated in order to improve the effectiveness and ideally create a robust track record in investigating and prosecuting high-level corruption cases in close cooperation with the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO).

Since the likely outcome of the elections may be a fragmented parliament with ensuing complex coalition-making efforts, the reform in the anti-corruption sector has a bearing on the essential reform efforts in the independence of the judiciary. These reforms most prominently involve the introduction of a mechanism for accountability and criminal liability of the Prosecutor General and the appointment of the Parliamentary quota of the Supreme Judicial Council. If Bulgaria witnesses a hung Parliament with deadlocked coalition, initiatives requiring Constitutional amendments, may be a long, if not impossible, shot at this moment. There would simply be no political will to garner the needed super-majority. In such circumstances, the push for revamping the Anti-Corruption Commission with investigative powers might be a plausible alternative along with an active EPPO on the ground for the reformist, pro-EU parties. In the alternative, if the next Parliament has a short life, a reflection of the political pickle of continuous electoral cycle and inability to have a functional Parliament and government, then the next interim Government would be facing difficulties in implementing the RRF reforms and the EU’s Rule of Law Report recommendations. This on its hand may lead to further backsliding in the rule of law and anti-corruption efforts in Bulgaria, further destabilization and political impasse and potential response by the EU institutions.

Dr. Ivo Gruev, Re:constitution Fellow 2022-2023, Postdoctoral Fellow, Centre for Fundamental Rights, Hertie School

Media Freedom

The dire state of press freedom and plurality in Bulgaria – ranked second last in the EU – plays a key role in swaying and distorting public opinion and political discourse. Media oligarchs with close ties to those in power benefit from the poor regulation and monopolisation of the media landscape. In return, the major media outlets tend to be uncritical or outright favourable of the political status-quo that effectively established a culture of kleptocracy, clientelism and cronyism, and trusted Bulgaria into economic and energy dependence on anti-European, illiberal actors. In the context of the current geopolitical crisis, mass media also regularly provide platform for narratives that reject to condemn Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and that advocate a pro-Kremlin and anti-EU, anti-NATO alignment for Bulgaria. Usually presented under the guise of ‘alternative point of view’, such rhetoric, which is not necessarily representative of public opinion, is becoming particularly pervasive ahead of the forthcoming general elections.

Prosecutorial Independence

The Bulgarian Procurator General (PG) deserves the attention of all observers concerned about the separation of powers and rule of law in Bulgaria. The PG is a de-facto unaccountable office inherited from Bulgaria’s communist past with significant influence and unfettered supervisory powers over the country’s criminal justice system. Its impunity has been repeatedly acknowledged by the ECtHR, the Venice Commission, The CoE’s Committee of Ministers, and in the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism reports of the European Commission. The current office holder, Ivan Geshev, was appointed in 2019 for a term of seven years with no effective competition: he was the single candidate for this powerful post, nominated by the then-ruling party GERB, which is also predicted to win the general elections on 2 October. It remains to be seen whether Bulgaria’s next ruling majority will attempt the long-overdue reform of this office, which, if left unaccountable, bears the risk of servicing the executive by failing to investigate high-level corruption allegations against prominent figures within Bulgaria’s political establishment.

Democracy Reporting International (DRI) works to improve public understanding of the rule of law in the EU as part of the re:constitution programme funded by Stiftung Mercator. Sign up for DRI’s newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter to find out more about the rule of law in Europe.